Court throws out convictions after forged breathalyzer documents surface; statewide breath test moratorium

On January 13, 2020, the Michigan State Police (“MSP”) declared every evidentiary breathalyzer in the State of Michigan compromised and unusable. The contractor responsible for calibrating the machines falsified certification records, making test results from those devices inadmissible in court. Although the criminal fraud investigation has only just begun, the MSP has identified 52 drunk driving cases that have been compromised, and at least 12 of those cases have already been dismissed.

On January 13, 2020, the Michigan State Police (“MSP”) declared every evidentiary breathalyzer in the State of Michigan compromised and unusable. The contractor responsible for calibrating the machines falsified certification records, making test results from those devices inadmissible in court. Although the criminal fraud investigation has only just begun, the MSP has identified 52 drunk driving cases that have been compromised, and at least 12 of those cases have already been dismissed.

The situation is dripping with irony. Someone’s scheme to avoid an afternoon of work, pretending it was already completed, created a statewide crisis that investigators, judges, attorneys, administrators, law makers, and untold others will spend countless hours fixing. Nevertheless, allowing unmonitored drunk drivers back on the road is a serious matter. Courts will not be able to mandate treatment for individuals convicted of Operating While Intoxicated (“OWI”), foregoing a critical opportunity for judicial intervention into a serious public health concern.

Most people are familiar with an intervention, where friends and family gather together to try and convince someone to accept treatment for a substance use disorder. Well, a large number of successful interventions are conducted under judicial supervision. When first detained, the suspect will be under constant observation by law enforcement. When the suspect is subsequently released on bond, he or she will be subjected to community monitoring, including regular alcohol and drug testing. Prior to sentencing, most courts conduct a substance abuse evaluation, where an experienced social worker evaluates the defendant’s substance use disorder(s), if any. Armed with the results of the evaluation, courts will order proportional and targeted treatment during sentencing. The underlying threat of a probation violation and possible jail time for non-compliance motivates compliance with treatment.

The criminal justice system has come a long way in how it views drunk driving. Drunk driving was once a minor offense, but in the 1980s, groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (“MADD”) successfully lobbied state governments to dramatically increase the punishment for driving under the influence. At the same time, policing underwent significant change. Violent crime and police fatalities were at record highs—in 1980, police were dying in the line of duty four times faster than today. A wedge separated police from the communities they served. That separation, together with the political environment, led to strict and stiff prosecution of OWI cases. The drunk driver was deemed a criminal who deserved serious sanctions. In addition to the judicial sentence, society also exacted a price in social and professional standing.

Over the last 20 years, however, empirically supported research has proven substance use, including alcohol, is not an issue of criminality. Rather, it is a public health issue. This realization has changed the way we deal with drunk drivers. A sign of this change is the establishment of sobriety courts across the country, where participants are court ordered to undergo aggressive treatment for two to three years. Across the board, sobriety courts save money, dramatically lower recidivism, and ushers participants into community, rather than the alienating them as criminals.

For every person who avoids prosecution, our society losses an opportunity to address a public health crisis. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services estimates the annual economic cost of excessive alcohol consumption to be $8.16 billion based on the last census in 2010. This figure includes expenditures related to crime, motor vehicle crashes, jails, healthcare, lost work productivity, and death. The breathalyzer scandal will only increase those costs.

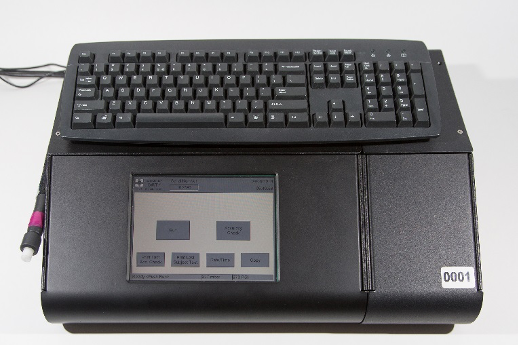

Three individuals were responsible for monitoring, servicing, and calibrating Michigan’s 203 Datamaster DMT breathalyzer devices. The company employing the technicians, Intoximeter Inc., has managed Michigan’s Datamaster devices for over 20 years. The company is presently paid $1.26 million per year for its services, which are absolutely critical to law enforcement. Calibration is the only way to ensure test results are accurate. Consequently, for breathalyzer results to be admissible in court, the instrument measuring the blood alcohol content (“BAC”) of the test subject must be regularly serviced, calibrated, and certified.

The machines in question are not the handheld devices used roadside during a traffic stop, which serve a much different role than Datamaster instruments. During a traffic stop, a police officer will use a preliminary breath test (“PBT”) device to measure BAC. A PBT is a portable, handheld device that quickly tests BAC levels. If a PBT reveals a suspect’s BAC is over the legal limit, there is probable cause to make a lawful arrest. However, PBT results cannot be brought before a jury in a criminal trial. Consequently, police will use a Datamaster to conduct “evidentiary testing”—testing that can be admitted into court—when booking a suspect at a secure facility. In contrast to the handheld PBT device, a Datamaster looks like an oversized typewriter with a hose protruding from its side.

The main cause of inaccurate tests is the presence of alcohol or other substances in the mouth of the subject. To ensure accurate testing, protocols require a 15-minute observation period prior to administering the test. The observing officer makes sure the suspect does not smoke, drink, eat, or put anything into his or her mouth that could affect the test. Officers are even trained to watch for regurgitation because alcohol expelled into the mouth increases BAC levels. The entire process is typically conducted under video surveillance. Following the test, police observe the suspect for a second 15-minute period before performing a second test. If the results of the second test are substantially different than the first, a third test is performed. In the event all three test results are inconsistent, the suspect must then be blood tested. Now, with the all of the State’s Datamasters offline, blood testing is the only route to secure an admissible BAC test.

Datamasters also undergo regular maintenance. Each device is tested on a weekly and monthly basis. Periodic testing is generally performed by one of the department’s police officers certified to conduct the tests. In addition to testing, the Datamaster must be calibrated every 120 days, which involves conducting a number of tests and documenting the results. If the test results meet the appropriate standards, the instrument is certified.

Investigators believe at least one of the three contractors certified Datamasters that were never tested. Someone copied data from old calibration reports and pasted the results into reports for neglected Datamasters. In other cases, Investigators found evidence that a contractor forged passing calibration results in the same way to pass Datamasters that actually failed control testing.

At both the state and local level, law enforcement appears to be addressing the issue quickly, with the MSP scrambling to both review all of the historical certification records, as well as properly calibrate each of the 203 machines. The manner in which any tainted cases will be handled remains to be seen. Van Buren County, venue for the twelve dismissed cases, has elected to err in favor of constitutional rights. All but one of the cases had been adjudicated—the remaining case was open because the defendant skipped town. The county canceled the absconding suspect’s arrest warrant and dropped the charges—which almost sounds like a reward for eluding law enforcement.

Although judicial grace was extended to the 12 cases in Van Buren County, further investigation may reveal much more challenging cases. What if the next case is a habitual drunk driver, putting an eighth or ninth notch on the belt? Even if the BAC percentage were not exact, the evidence would still demonstrate that chronic drunk driver was behind the wheel intoxicated. Should the chronic drunk driver be released? Even more challenging, what if a driver killed a pedestrian, a child pedestrian? And what if the BAC level was just over the legal limit? What if the nature of the collision was such that it could have easily been a tragic accident rather than a crime, but for the illegal level of alcohol in the driver’s blood? Now, a court may have to decide whether setting that driver free is constitutionally required. On one hand, a court could affirm the conviction, despite the fact the driver very well could have been under the legal limit and but for the fraud of Intoximeter, would have been innocent of any crime. On the other hand, a court could set aside the conviction. However, someone would have to tell the deceased child’s mother that the person responsible for their child’s death was being set free on a technicality.

The reality is that more dismissals are likely—and a number of drunk drivers will walk away without treatment or punishment, but in my opinion, that is the proper outcome. There’s an old saying that courts should be wary of letting a good case make bad law. In this situation, that means not letting a good case for ignoring evidentiary rules create a precedent of admitting marginal, compromised, or misleading evidence in criminal prosecutions. Disregarding constitutional protections, even where guilt is apparent, is the first step towards ceding our individual freedoms and liberties to the prosecutorial whims of law enforcement.

By Benjamin W. Bryant, J.D.

Neumann Law Group

Source Material:

- Correspondence from Major Greg Zarotney, Michigan State Police Office of Professional Development, to Michigan Prosecutors and Law Enforcement Agencies, dated January 10, 2020;

- “MSP Statement on Temporarily Suspending Use of Data master DMT in Wake of Criminal Investigation into Contractor Malfeasance,” Michigan State Police website, published January 13, 2020;

- Michigan Preliminary Breath Testing Training Manual 2018;

- “Excessive Alcohol Consumption; Economic Costs, Michigan 2010,” Michigan Department of Health and Human Services fact sheet, 2010;

- “Michigan State Police breathalyzer probe finds issues with 52 drunken driving cases,” article by Gus Burns, mLive.com, January 16, 2020;

- “Michigan State Police finds flaw in breath alcohol testing, suspends contract,” article by George Hunter, Detroit News, January 11, 2020; and

- “Michigan State Police launches criminal investigation after possible flawed breathalyzer test results,” WXYZ.com, January 14, 2020.

- “12 drunken-driving cases dismissed,” article by David Panian, Daily Telegram News Editor, January 18, 2020.